Six questions to ask before agreeing to a software audit clause

An audit clause within a software agreement is the mechanism used by software publishers to instigate a software audit.

Software is not “owned” but instead customers buy the “right to use” software. This right to use has terms and conditions, typically laid out in the software agreement. The audit clause is their way of checking you are adhering to the terms.

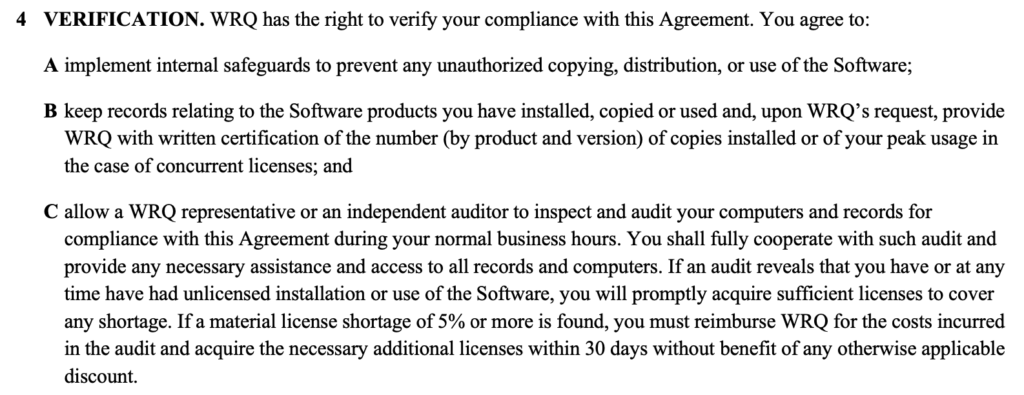

For example, here is an old software audit clause from a WRQ software agreement:

As you can see. The customer signing this agreement has to put safeguards in place to manage the IP it is buying access to, keep records and cooperate with a software audit.

If the audit result deviates by more than 5% from what is expected, the customer will need to pay for the cost of the audit and buy the missing software without any discounts applied. (This is why many organisations aim for a 95%+ accuracy rate for ITAM data).

It’s a bit like renting a house and accepting an inspection from time to time, or buying a rail ticket and having it inspected whilst you travel. However in terms of right and wrong, defending a software audit is closer to Law or Taxes, in that there is right, wrong and 50 shades of interpretation in between. Hence the need for “Audit defence”.

To manage risk it is recommended that customers perform a “dress rehearsal” or periodic internal practice audit from time to time to prevent any surprises during a real audit and hone their processes. To facilitate this you’ll need to replicate the audit and be able to calculate as the publisher would.

To prevent abuse of the audit mechanism and allow customers to be self sufficient and adhere to the audit terms, I recommend asking the following questions before agreeing to an audit clause:

- CODE OF CONDUCT – Ask the software publisher to share the professional code of conduct for executing the audit clause. If the audit is conducted by a third party, what code of conduct is the third party bound by? Asking this question gives customers an opportunity to raise objections to sloppy or unprofessional behaviour and escalate it accordingly. A sample code of conduct can be found here: https://clearlicensing.org/audit-code-conduct/

- FEEDBACK MECHANISM – Ask them if customers are involved in the improvement of license and audit programs. Software audit programs have been built by software publishers to protect their IP. It should evolve as it meets with customers to ensure it is fair and realistic. How can you provide feedback?

- SELF SUFFICIENCY: Are the details of license programs, software agreements and licensing metrics freely available online in the public domain? A customer shouldn’t be held to ransom against rules that are not known or freely available or explicitly detailed in the contract

- PUBLIC DOMAIN MEASUREMENTS: Are license metrics in the public domain? It would be a bizarre world if we were stopped for speeding driving on the road when the speed limit was not known or defined. A customer should be able to measure their own compliance against publicly known license metrics, achievable with everyday tools. They should be able to replicate the audit internally. Otherwise audit clauses are a form of entrapment.

- WHAT IS AN AUDIT? Has the publisher made it crystal clear what an audit request is? How will it be initiated? How is it differentiated from a sales scoping exercise or review? What protections are in place to prevent abuse of the audit clause? What choices does the customer have and how can they tell the difference?

- UNREASONABLE REQUESTS – How does the software company handle software audit requests that arrive at a bad or inappropriate time? Organisations operating in seasonal markets might have internal network “lock downs” when nothing can happen to production systems (such as online retail in the run up to Thanksgiving and Christmas) or you might already be wrestling with three other audit requests. How is this handled?

As stated on the first term of the WRQ audit clause above, customers need to “implement internal safeguards” to manage the IP they are renting access to – which is the development of a modern ITAM practice.

An audit request can be thwarted by periodically presenting a compliance position to publishers before it’s even requested or having a reputation for excellent ITAM. Audits are a costly exercise for publishers and they will readily skip your audit if they think it’s going to be a waste of time. Independently proving the quality of your ITAM practice is something the development of the new certification program for ISO/IEC 19770 will unequivocally demonstrate.

If you have any other recommendations please contact me or leave a comment below.

Thanks, Martin

Related articles:

About Martin Thompson

Martin is also the founder of ITAM Forum, a not-for-profit trade body for the ITAM industry created to raise the profile of the profession and bring an organisational certification to market. On a voluntary basis Martin is a contributor to ISO WG21 which develops the ITAM International Standard ISO/IEC 19770.

He is also the author of the book "Practical ITAM - The essential guide for IT Asset Managers", a book that describes how to get started and make a difference in the field of IT Asset Management. In addition, Martin developed the PITAM training course and certification.

Prior to founding the ITAM Review in 2008 Martin worked for Centennial Software (Ivanti), Silicon Graphics, CA Technologies and Computer 2000 (Tech Data).

When not working, Martin likes to Ski, Hike, Motorbike and spend time with his young family.

Connect with Martin on LinkedIn.

Hello Martin,.I agree your points and these are very true. In case if the audit results in less than 5% non-compliance, we can put a clause stating that publisher should pay the customer the compensation of loss on time spent during the audit.